Diet culture...at the eye doctor?

Why I had to write a letter to my optometrist—plus some anti-diet gifting tips

I’ve come to accept that diet and weight talk shows up just about everywhere and is especially common in medical offices. Yet somehow I never expected to hear I should cut out entire food groups while having my eyes examined.

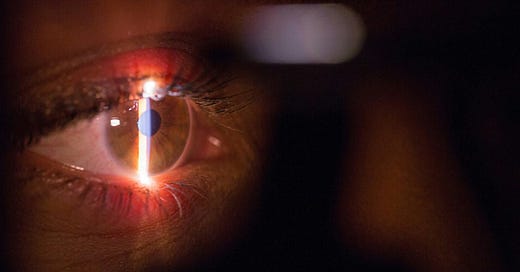

At my annual vision check, I mentioned some increased light sensitivity, especially at night, and I wondered how much perimenopause and aging in general might be a factor. My doctor suggested it might be “inflammation” that could be addressed through “clean eating” and specifically the Whole 30 diet.

Reader, I almost fell out of that elevated exam chair.

I don’t remember exactly what I said next, but it was something about not being interested in dietary restriction. And I couldn’t help but point out that this kind of recommendation could be harmful for a lot of people.

I wasn’t terribly articulate in the moment and didn’t want to “protest too much.” So I decided not to ask for evidence supporting a restrictive diet for photosensitivity, let alone question the ethics of an optometrist offering nutrition advice.

I didn’t share I had already learned the hard way about the risks of making one-size-fits-all dietary changes for suspected inflammation.1

We also didn’t discuss the fact that most people with astigmatism experience intense glare while driving at night, especially now that every car seems to have those too-bright LED headlamps. Cutting out foods isn’t going to change auto industry standards or the shape of my eyeballs.

The good news was that my doctor seemed to accept my passionately awkward response and didn’t double down; instead, she offered some practical ideas that might actually help my vision at night. Phew!

When I shared this experience on an Instagram story a few weeks ago, I heard from so many people who had faced similarly upsetting talk in unexpected places.

Diet culture is truly everywhere.

A lot of folks insisted I find a new doctor, a common recommendation when someone shares a story like this. Changing providers sometimes is exactly what’s needed, but it’s not always possible or easy. Even if you have the luxury of switching doctors, there are rarely guarantees you won’t experience something similar in another office.

If you have a decent relationship with a medical provider, and they’re on your insurance and reasonably close, there are a lot of compelling reasons to stick with them. It might mean setting some boundaries (e.g., declining to be weighed unless truly necessary) or finding ways to cope with the inevitable weight stigma or wellness woo you might be exposed to while you’re there.

Sometimes you want to go beyond just protecting yourself. In the case of my eye doctor, I felt she might be open to learning something new. And because I know so many other people who go to her, I felt an extra level of responsibility.

I’m not normally a fan of sending a long email or letter about these sorts of things. I mean, writing one can feel great, but actually sending one doesn’t tend to be terribly effective if you’re hoping to have a good working relationship with the recipient. I think this is especially true when it comes to communicating with teachers.

But sometimes it’s hard to say everything you want to say in person, especially with the power differential between doctors and patients. And in those quick appointments, there isn’t usually time for meaningful conversation anyway.

Sometimes a written document can be useful—ideally, as part of ongoing communication. In case it’s helpful, I thought I would share what I wrote to my eye doctor. I’ve removed a few personal details, but you’ll get the gist.

It’s more lecture-y than I would like, but in this situation I felt compelled to go into Educator Mode even while risking the written version of Teacher Voice:

December 2, 2024

Dear Dr. X,

Thanks again for taking time at my last appointment to discuss some of my larger health concerns that may be having an impact on my vision. I wanted to follow up to share a bit about why I reacted the way I did to the recommendation to make dietary changes. I didn’t express myself very well in the moment, so I wanted to write you this letter so I could share a little more.

I know you only want to help your patients, and I sense you might be open to learning about why dietary restrictions may not be safe for many of the people in your office.

In my work in the eating disorder field, I have learned that a common catalyst for disordered eating is a comment from a doctor. We hear diet advice all the time in our culture (especially here in LA), of course, but words from a medical professional carry a lot more power.

A desire to “eat healthier” or “eat clean” has become one of the most common eating disorder origin stories. I see families almost every day who are fighting for their child’s life, when only a few months ago their teen or young adult just wanted to “eat healthier.”

And it’s not just adolescents who are at high risk. Women in midlife are also especially vulnerable to eating disorders. And eating disorders affect boys and men, too, with rates rising rapidly. A recent study showed 1 in 7 males will experience an eating disorder by age 40; it’s 1 in 5 for women in their lifetime.

Cutting out food groups or becoming afraid of certain foods can be a recipe for disaster and the opposite of health-promoting for people at risk for an eating disorder or relapse—and the tricky part is that you can’t tell who those people might be. Contrary to popular belief, eating disorders don’t have a “look,” and all eating disorders can affect people in all body sizes.

The desire to address health problems with food can be so seductive, especially when natural approaches tend to feel safer. And for people with allergies, celiac, or other conditions (including known nutritional deficiencies), specific evidence-based dietary changes can absolutely be powerful interventions. Blanket recommendations for elimination diets or other restrictions, however, can end up being counterproductive for health and wellbeing.

Thanks for reading, and I hope we can continue the conversation at my next appointment. I’m happy to answer any questions or provide additional resources in the meantime.

Sincerely,

Oona Hanson

Assuming I get to have a follow-up conversation, I’ll report back. And if it doesn’t go well, I can always return to another eye doctor I’ve seen before. Having this safety net is probably why I felt confident expressing myself so directly. I know this approach won’t work for every situation.

Want more support navigating awkward medical appointments?

Communicating with doctors about these issues can be intimidating and exhausting, especially if you’re in a larger body. If you want scripts and tips for these situations, check out the Weight and Healthcare newsletter from

.If you have a child recovering from an eating disorder, you may have discovered the pediatrician’s office can feel particularly problematic. Even patients who’ve required hospitalization for anorexia can be faced with a doctor’s concern about gaining “too much” or eating the “wrong” foods. If you’re in this situation, I hope this essay, “The Conversation You Need To Have with the Pediatrician,” provides some useful ideas.

In case you missed it

I don’t have a holiday gift guide, but I do have thoughts about ways to avoid a common gift-giving pitfall.

In my latest piece for CNN, I talk about why to think twice before giving someone a fitness gift—and some special considerations for children. For example, Fitbits and other wearable technology can be particularly risky for adolescents because, as therapist Carolyn Comas puts it so vividly, “it’s like a little eating disorder brain on your wrist.”

You’ll find more great insights from her as well as from

in this piece:Thanks for reading during this busy time of year, and let me know if you have any questions.

If you want a deep dive into the evidence around anti-inflammatory diets, you might appreciate Dr. Laura Thomas’s recent exploration of this topic.

Love your letter. I submitted a comment to my daughters’ pediatrician following their last appointments. This doctor was great at helping my older daughter (17) through an eating disorder several years ago, and her comments this time were great and very sensitive. When my 14yo daughter (who is taller and thinner) had her time with the doctor, the doctor showed her her growth charts and praised her for growing well and having a weight that “looks great”. My youngest thankfully makes no extra effort to have a “good weight”. I don’t necessarily think this doctor would label someone’s weight as “bad”, but I wrote her to say she should reconsider labelling anyone’s body or weight as “good” or as anything at all. My youngest’s body will change and possibly into a form that is not deemed as “good” as it is now. Just setting her up for bad feelings if her body changes or sometime later doesn’t get the same glowing report from the doctor or anyone else. It’s a never ending fight….

Wow, that's ridiculous. I went for an eye exam recently for the first time in years, and I learned that I have a little bit of inflammation and that this is typical with age and generally increases over time. It is baffling that your doctor gave you this bogus nutritional advice, but I guess I'm not surprised!