One of my favorite quotations is attributed, perhaps erroneously, to Albert Einstein:

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

In diet culture, counting things—steps, calories, protein grams—seems to matter a lot.

And for many of us, the numbers themselves can start to take on an unhealthy life of their own despite the rebranding of dieting as wellness and self-surveillance as biohacking.

Wearable technology has only amplified the desire and sense of urgency to collect data about our bodies—and it’s raised the risks, too.

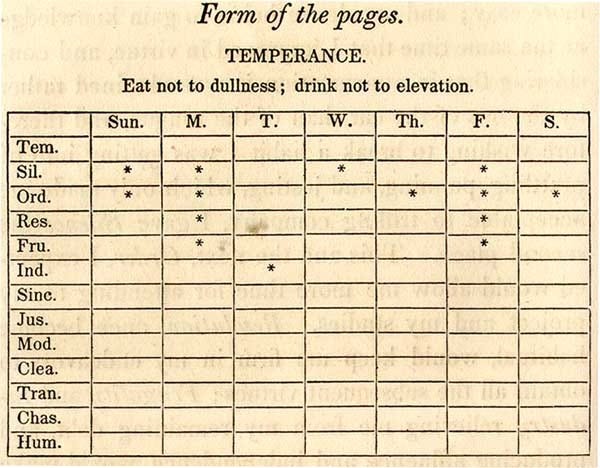

Documenting daily behaviors, including food intake, isn’t exactly new. In the 1700s Benjamin Franklin recorded and later published his pursuit of “moral perfection.” Though he wasn’t tracking his weight—bathroom scales wouldn’t be available for about another two hundred years—he did monitor his food and alcohol consumption.

You might say Ben Franklin’s Autobiography walked so Bridget Jones’s Diary could run.

Once calorie-counting in pursuit of weight loss became popular, dieters were advised to keep a written account of meals and calculate caloric intake. Long before Weight Watchers rebranded as “WW: Wellness that Works,” it was already innovating its marketing when it launched the concept of “points”—“you don’t even have to count calories!” (I could probably write a whole essay on the concept of “zero-point foods.”)

What happens when you spend a lot of time recording what you ate and calculating calorie or point totals?

If you’ve ever done it, you already know.

It changes your relationship with food, sometimes forever.

Whether you’ve experienced an eating disorder or simply dieted multiple times, you might find your mind automatically sees food as inextricably linked to a numerical value. Even if you’ve done a lot of work to reject the calorie-counting mindset, you can’t just un-know what you were trained to learn by heart.

Carefully tabulating every bite and every minute of exercise is itself a common symptom of an eating disorder. And the very act of tracking can also trigger a troubled relationship with food and movement.

When eating and exercise are reduced to a math problem, food and movement stop being something to experience physically, in the body, but rather something to be monitored, controlled, and analyzed from the outside.

For many, this change is what introduces disorder into the system. It’s why giving food journal assignments in school is so risky.1

Shifting from pen-and-paper to apps like MyFitnessPal took this kind of diet monitoring one step further. And now with the ability to scan barcodes and estimate calories from a photo—all while every movement and blood sugar change are being captured by a device—the process of tracking food and activity has become even more mechanized.

You don’t even have to do math or make decisions based on your calculations. You no longer get to self-assess your “virtues,” like Ben Franklin did. And you definitely don’t need to listen to your body. Instead, an app keeps the score.

This volume of information and its gamification can be exciting and fun, at least at first. Lots of people report feeling better when they start adding more movement into their day based on their tracker’s prompts. Precise physiological measurements may offer elite athletes that split-second training edge that helps them make the Olympic team or earn a medal. And for those with certain medical diagnoses, such as diabetes or specific heart conditions, real-time health data can be truly life-saving.

But for many of us, the numbers themselves and the constantly moving fitness goalposts can leave us overwhelmed and weighed down with a sense of never quite measuring up. While many adults use wearables to try to enhance their drive to exercise, the irony is that falling short of fitness goals can end up undermining our motivation to be physically active. Feeling defeated by neverenoughness doesn’t incentivize us to move and can take a toll on our overall wellbeing.

Others may find themselves becoming obsessed with the data and feeling compelled to follow orders from the mini computer attached to their body—even when it’s doing them harm. Exercising despite illness, injury, or dangerous weather conditions; forgoing time with friends and family; ignoring hunger cues—all to satisfy a machine.

The potential downsides to wearable technology make these devices especially risky for young people.

Adolescents are more concrete in their thinking and so are even more vulnerable to seeing things in all-or-nothing terms. The health apps aren’t necessarily known for their flexibility and nuance.

A young person who tunes out their body’s signals and follows a one-size-fits-all protocol can end up in peril because their need for calories and rest are so high.2

Remember that getting into energy deficit, even by accident, can be the start to an eating disorder.

When I interviewed therapist Carolyn Comas for a CNN article about buying fitness gifts, something she said has stayed with me ever since. As she put it, a wearable tracker is “like a little eating disorder brain on your wrist.”

If you happily use a Whoop, FitBit, or Apple Watch, this statement probably sounds extreme. But there’s a reason eating disorder professionals see danger in these devices, especially for young people and others who are vulnerable. Nearly every day, someone in their office shares how their illness started with tracking steps or calories—or the way they feel controlled by an outside voice telling them how to eat and move.

“It’s like a little eating disorder brain on your wrist.”

Young people’s brains are literally still developing, and they are in a crucial stage of identity exploration. Adolescents are building the cognitive, social, and emotional skills that will be the foundation for the rest of their lives.

These devices can warp someone’s relationship with food, exercise, and their body. In addition, a focus on numerical data can start to take up more and more space in a young person’s sense of self and even self-worth. A fixation on “closing rings” or following rigid nutrition goals can crowd out time and energy for doing all the other things that could enrich their lives.

The popularity of these products raises an even bigger question about their effect on future generations:

What happens when young people miss out on opportunities to practice being attuned to their own bodies, their preferences, their pleasure, their intuition?

Against the backdrop of the unregulated AI industry, more and more people are voicing concern about the risks of outsourcing our judgment, atrophying our ability to think, to write, to create, to connect.

The costs of surrendering our own knowing and over-reliance on quantifiable validation are on a lot of people’s minds right now. In just the last week, I’ve read

’s piece about Substack itself and heard and explore the risks of invalidating your own opinions, as they darkly joked about asking ChatGPT, “What do I think?”3And when it comes to young people’s relationship with their own bodies and minds—and how they take care of them—the stakes are pretty high.

Inner wisdom and intuition aren’t just about knowing things. It’s about knowing you know, without needing to double check with an outside source.

If we delegate our confidence and body trust to a device, we can lose connection with own inner compass, threatening the most intimate and longest relationship we will ever have: with ourselves.

Everyone with a smart watch or Oura Ring isn’t doomed to develop an eating disorder or completely lose touch with their instincts. But it’s worth considering the hidden costs that come with kids and young adults missing out on learning what their bodies need and enjoy without a bot deciding for them or scolding them for falling short.

To repeat: it’s not that tracking devices and apps are universally problematic. As with just about anything we interact with daily—food, technology, you name it—it’s not that the thing itself is inherently good or bad; what matters most is our relationship to that thing.

You could absolutely use a step-counter or a movement-reminder app in a way that supports your wellbeing and doesn’t become disordered. Even though Ben Franklin gave himself strict rules—“Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful.”—he also considered it a virtue to “avoid extremes.”

If your child is already using one of these wearables, it doesn’t mean you need to go yank it off of them. But it’s worth staying aware of the risks, paying attention to how your child relates to the device, and being honest with yourself about how you’re modeling the use of health data.

Keep in mind that your teen doesn’t even need to own a specific fitness device to get some of this information. Many cell phones come with built-in health apps that track steps and calculate estimated calories burned through movement.

After a recent update on my phone, some default settings must have changed, and a notification popped up on my screen: “You’re burning fewer calories this week.”

My first thought was about all the people trying to recover from an eating disorder for whom that kind of message could be incredibly harmful. And then I wondered, how would that message feel to a teen taking much-needed rest because of an illness or injury? Or to a young adult who has decided to unplug and not to keep their phone on them at all times in order to support their mental health?

You’re probably already talking as a family about technology and its role in our lives. If you want to touch on health tracking specifically, here are some possible conversation starters you might try with your teen:

What do you think of people having all of this data at their fingertips?

Which aspects of our health could never be captured by a device?

When it comes to our wellbeing, how much do these numbers really count?

Latest Podcast Appearance

I was recently a guest on the Progressive Parenting Project Podcast where we talked about practical body-affirming strategies and larger abstract concepts like self-compassion. Contrary to what you might assume, host T.J. Campbell doesn’t use the term “progressive” in its political context but rather as a larger framework for thinking about how we can all make progress in nurturing ourselves and others.

Have a question about raising resilient kids in diet culture?

I will be answering reader questions (you can remain anonymous) in upcoming newsletters. If you’re a subscriber who received this newsletter in your in-box, simply reply to the email. Or you can submit questions through this contact form.

Because there’s always nuance here, note that some people find food journaling helpful, at least in the short-term, for things like identifying migraine triggers or even supporting certain stages of eating disorder recovery, when supported by a professional.

Another nuance alert: For those who don’t have reliable access to internal body cues because of medication, neurodivergence, or a medical condition, technological systems and reminders to eat can be incredibly helpful.

Have you heard about MIT’s study on the “cognitive debt” incurred by ChatGPT users? It confirms the main reason I do not use generative stolen, derivative AI in my writing.

Thanks for this. You bring up so many important points. I’ve drawn a line at smart watches for my kids and teens, for all the reasons you’ve mentioned. They haven’t always agreed with me, but I hope one day they see why!

I am bookmarking this so I can share it in the future with my therapy clients. I've been trying to tell clients for YEARS that their fitness trackers aren't helping them, but people are so skeptical and dismissive because trackers have become so ubiquitous. My other pet peeve as a therapist is people telling me they have insomnia because their tracker tells them they're not getting enough "deep sleep" or underestimates the number of hours they are sleeping. I have heard some version of this countless times: "I thought I got eight hours last night, but the tracker said I only got five. How can I get more sleep?" I question why they believe the feedback from a flawed device instead of their own perception. The worry this creates absolutely contributes to an increased sense of fatigue. It's like their watch is gaslighting them, but most people refuse to take them off.